Napnü Reference Document 2024

Qunasmakhë Pënwü

Napnü Reference Document

Winter 2024

Contents

1.3. Neigboring Languages & Cultures 6

1.4. The Name of The Language 7

2.1. Realization & Allophony 10

2.3. Phonotactics & Prosody 10

2.5. Phonological Processes 12

2.5.2. Consonant Alternations 12

3.3.4.1. Modal Construtions 20

3.4.1.2. Nominal Person Prefixes 23

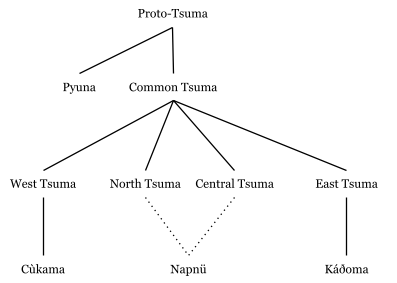

Napnü is a daughter language of Common Tsuma, the language of the Tsuma peoples as spoken from year 500 to year 1000. In universe, Napnü is spoken from around 1700 and onwards. The language retains many features from its ancestor, but its overall grammar and phonology has changed considerably.

I started trying to create a daughter language for Tsuma back in October of 2023 (i.e. a year ago). This proved difficult, mostly because I didn't have the proper momentum to develop it further, but also probably because I was still busy working on Tsuma. My initial ideas were quite different from this version of Napnü. Initially I wanted it to be a tonal language, spoken in the mountains north of Tsuma’s urheimat. This version of Napnü is spoken in the western part of the Tsuma region, not far from where central Tsuma would have been spoken.

This section intends to give a brief overview of the language’s history and culture. It also seeks to summarize the neighboring cultures and languages which influence the Napnü language. Lastly, some information about the document itself is given at the end of the section.

Napnü belongs to the Tsuman language family, which is comprised of Common Tsuma, its descendents, and the sister language Pyuna.

Napnü’s exact possition in this tree is uncertain. It is clear that it didn’t descend from West Tsuma, since it lacks a reflex from the accusative suffix -gy (cf. Cùkama -c ‘ᴀᴄᴄ’). It instead has traces of the metastasized accusative <y> found in the other dialects, e.g. in the word himya ‘fish’ (< himyá ‘fish<ᴀᴄᴄ>’). Nor can the language come from East Tsuma, since it doesn’t show reflexes of the person form iti ‘3sɢ’ unique to East Tsuma (cf. Káðoma ide ‘2sɢ’). Instead, the third person singular is u from wo, the original form used in the other Tsuma dialects.

This means that Napnü must come from either the central or the northern dialect, or a mix of both. The remaining differences between the northern and central dialect aren’t big enough to give a clear image as to which dialect Napnü descends from. What may be the case, is that the north and east Tsuma speech communities retained a stronger connection over the years, causing the dialects to converge and eventually merge.

The history of Napnü begins with the colonization of the Tsuma region. For many hundred years the Liqak empire had tried to conquer this area, but the Northeastern mountain range made passage into Tsuma territories virtually impossible. But with the advent of advanced seafaring, the Liqak were able to move large armies across the ocean. This marked an end to the Common Tsuma era, and the Tsuma peoples were forced into a sedentary lifestyle, the polar opposite of their traditional way of life.

In this period, Tsuma siezed to be a prestige language. It was replaced by Empirial Liqak, and the administrations in the newly established towns used it as an official language. However, Tsuma continued to be used in all other domains of life. The Tsuma people’s long history of colonial resistance made them particularly resistant to change once Liqak did succeed in subjugating them. This allowed them to preserve their language, though it absorbed a lot of influence from Liqak.

The Tsuma region (or Sümrë in Napnü) gained independence after hundreds of years of continued efforts. This happened through violent resistance and by Tsuma people entering high government positions and influencing policy, but a key factor was the gradual collapse of the Empire around the year 1750. Napnü, the most commonly spoken descendent of Tsuma, was quickly made the official administrative language of Sümrë. Puristic language practices made sure to replace the many Liqak loanwords which had found their way into the language over the ages.

The Tsuma written language survived a couple hundred years into the occupation, but it eventually died out. Late Tsuma texts show traces of the kinds of sound changes that were happening to the spoken language. A cursive style of writing was also developed in the last 200 years of the Common Tsuma period. When Napnü was made the official language of Sümrë, these later Tsuma sources acted as a foundation. As such, Napnü writing shows some degree of etymological spelling.

The Tsuma peoples experienced a forced cultural shift when they were subjugated by the Liqak armies around 1000. They were made to transition from their traditional nomadic lifestyle to a sedentary one, and urban centers with modernized institutions were established. Because of this, the speakers of Napnü live similarly to other modernized peoples.

There are several languages in the vicinity of Sümrë. Káðoma is spoken to the east. The language is a Tsuman language with a strong Liqak substrate, but it shares many features with Napnü and is its closest relative. Another Tsuman language, Cùkama, is spoken west and north of Sümrë. Cùkama is, in contrast with its sister languages, highly analytical, and has few traits in common with the others.

Other unrelated languages are also spoken not far from the region. Sum, a Pakesian language, is spoken on the Pakesia Island south of Sümrë. To the far-east, Liqak is spoken. Due to its position as the official language of the Liqak Empire, it has influenced Napnü a great deal over the centuries.

The map below shows the current distribution of the Tsuman languages, i.e. the descendents of Proto-Tsuma. Other language families are not included.

Figure 1: The distribution of the Tsuman languages

Despite their proximity to one another, the languages have developed in very different directions. This is perhaps unexpected, considering how close they are to one another geographically. Because of this, other factors need to be sought out to explain how the languages diverged so much. The most obvious is the provincial divisions established during Liqak rule, which separated the Napnü peninsula into its own administrative region, while using the region where Káðoma is spoken as a military outpost. Cùkama likely arrived at its location when various Tsuman tribes fled the Liqak conquest to establish themselves in safer areas. They likely intermingled with pre-Tsuman cultures, which might explain Cùkama’s aberrant phonology and grammar.

The name of the language that I use in this document, Napnü (which can be segmented like na-panü) literally just means ‘our language’. But historically, the noun panü comes from the Tsuma word pánu, which meant ‘song’ or ‘music’. This is the most common term used by the speakers to refer to their language.

Within the culture itself, Napnü is seen as a colloquial term. In academic circles, the term sümya is preferred, which is a learned borrowing of the name Tsuma, nativized with sound changes and such. The unproductive infix <y> is present, since most nouns of this type derive from Tsuma accusative forms (CT tsumyá). In anology with the term Napnü, the possessive prefix na- is often applied to this term as well, yielding nasümya. This is what I’ve used in the title of this document.

Qunasmakhë Pënwü | |

qu=na-süma-khë | pënwü |

ᴅᴇғ=1ᴘʟ-tsuma-ᴏʙʟ | investigation.ɴᴏᴍ |

The word I’ve used in stead of document here, pënwü, is originally a resultative noun derived from the Tsuma verb ponu ‘to look into’, which meant ‘knowledge’ or ‘investigation’. A direct translation could be ‘Investigation of our Tsuman language’, which is how I decided to translate the more boring name Napnü Reference Document.

This reference document serves as a grammar sketch for the language. It is written from a diachronic point of view, often putting the contemporary grammar in the context of the ancestral language’s structure. Because of this, it assumes some prior knowledge about Tsuma.

All major dialect traits are described in the document. However, examples are mainly given in the largest dialect, which is spoken in the larger towns in the North. This dialect is not the most conservative, and corresponds rather poorly with the written language. Nonetheless, it has attained high status in Sümrë society.

Central Napnü’s consonant inventory is presented in Table 1. The Vowels are shown in Table 2.

Table 1: The consonantal inventory

Labial | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Pharyngeal | |

Nasal | m | n | ɲ | |||

Stop | p | t | k | q | ||

Fricative | f | s, z | ʃ | χ | ħ | |

Sonorant | (w) | l | j, ʎ | w | ||

Trill | ɾ |

Table 2: The vowel inventory

Front | Central | Back | |

High | i | ɨ, ʉ | u |

Mid | ɛ | ə | ɔ |

Low | a |

The original phonotactics inherited from Tsuma remain relatively unchanged. It still prefers CV-structures, but it now allows CC-clusters. This is not reflected in the written language, which represents the earlier phonotactics of the language. The syllable structure of the spoken language can be summarized as #(C(w/j))V(C)#. Not all consonant clusters are allowed and are simplified when they arized:

The old stress system was completely lost. Older forms of Napnü had no stress, but in the contemporary language the final syllable of prominent words are lightly stressed. This stress is realized as a slight lengthening of the vowel and with a high tone. Also, if the word has particular prominence in the sentence or it comes before a pause, the vowel of the final syllable will be held for significantly longer.

The romanization tries to be as transparent as possible by representing both phonemic and allophonic variation.

Table 3: Romanization

Grapheme | Phoneme | Sound | Example |

e | /ɛ/ | [ɛ] | re- |

ë | /ə/ | [ə] | hëri- |

f | /f/ | [f] | fëkuh |

h | /ħ/ | [ħ] | hawë |

ï | /ɨ/ | [ɨ] | ïmvü |

kh | /χ/ | [χ] | khëli |

lj | /ʎ/ | [ʎ] | tëlja |

nj | /ɲ/ | [ɲ] | njawë |

o | /ɔ/ | [ɔ] | ro- |

q | /q/ | [q ~ ʔ] | oqü |

r | /ɾ/ | [ɾ] | arë |

sh | /ʃ/ | [ʃ] | shyawïh |

ü | /ʉ/ | [ʉ] | ümkhë |

v | /f/ | [v] | ëva |

y | /j/ | [j] | yash |

This section discusses the phonological processes present in the phonology of the language. Common Tsuma is known for having a somewhat confusing (to me at least) system of metathesis and a system of consonant alternations. Napnü inherited this system, though it simplified much of it. Sound changes also gave rise to new vowel alternations, which created another layer of morphophonological complexity.

Prefixal metathesis is inherited pretty much without any changes, and is described in section 3.4.1.2. on nominal person prefixes. Suffixal metathesis is mostly lost in nouns, but leaves some traces in verbs, where it is still visible in the past tense forms which derive from the Tsuma perfective aspect, which will often surface as an infix <w> in the final syllable of the verb stem.

Words that had consonant mutation in Tsuma generally preserve these alternations in Napnü. In some cases, the alternations are regularized due to analogy. This most often results in the non-mutated stem suplanting the mutated stem, but sometimes the opposite occurs.

Vowels in Napnü are divided into “strong” and “weak” vowels. Weak vowels are derived from the Tsuma vowels /e, a, o, u/ when unstressed, which underwent vowel reduction in such environments. /a/ did not originally have an unstressed allophone, but later merged with unstressed /o/ into [ɐ]. [ə], the unstressed allophone of /e/, was consequently pushed to [ɨ], which dragged [ɐ] to [ə]. Around the same time, [ʊ] shifted to [ʉ] to match [ɨ]. Then, the originally stressed allophones of /e/ and /o/ were lifted to /i/ and /u/. The entire stress system was lost thereafter, meaning the conditioning environment for all these allophones was removed. This turned them into new separate phonemes.

This resulted in odd vowel alternations in Napnü, which vary depending on the stem type. As with Common Tsuma, three main stem types can be identified: O-stems, E-stems and bare stems. These are preserved in Napnü as U- and I-stems respectively, but they have been split into strong and weak sub-classes depending on how they were impacted by vowel weakening. When a stem is refered to as weak, it essentially means that the stress used to be mobile, and therefore vowel qualities would change inside the root. Note that original /i/ do not weaken, but /i/s derived from CT /e/ do.

Table 4: Vowel alternations

Strong | Weak |

a | ë |

u¹ | ë |

u² | ü |

i¹ | ï |

i² | i |

The effects of these alternations are most visible in the declension and conjugation patterns of weak bare stems. This group consisted of disyllabic roots with short open syllables. These were prone to stress shifts when various suffixes were attached. This variation is illustrated in the table below.

Table 5: Vowel alternations

Penultimate Vowel | Final Vowel | ||

Imperfective | Strong | Weak | |

Perfective | Weak | Strong | |

Inchoative | Weak | Strong | |

Imperfective | Weak | Weak | |

Perfective | Weak | Strong | |

Inchoative | Weak | Weak | |

Derivational form | Weak | Strong | |

Dissimilation occurs regularly in plurals of nouns, which are formed through partial reduplication. Generally, the consonant of the reduplicated syllable will retain its original quality, while the onset of the root will lenited, i.e. from stop to fricative or fricative to sonorant. In the case of /z/, it is softened to /ɾ/, and /ɾ/ is softened to /l/. E.g. zak ‘hand’ > zarak ‘hands’. This is explained in greater detail in section 3.2.3.

Vowel syncope occurs when two consonants are followed by and separated by a vowel, in which case the vowel separating them is dropped. This happens very regularly and across word boundaries. This process can be described as such: VCVCV > VCCV. Depending on what sounds are involved, the cluster will simplify: [1] The fricative /f/ will assimilate in voicing to the previous or following consonant. [2] The stop /q/ will assimilate to /k/ before /k/ and likewise the other way around, meaning that the clusters */qk/ ans */kq/ become /kː/ and /qː/. [3] Sibilant consonants will assimilate in voicing when before another sibilant, such that */sz/ will become /zː/ and */zs/ will become /sː/.

The Napnü stem system is based on the thematic vowels used in suffixes. The different stem types are: Strong U-stems, weak U-stems, strong I-stems, weak I-stems, strong bare stems and weak bare stems. The division of strong and weak syllables is based on vowel weakening; when the stress of the word was mobile in Tsuma, the suffix would attract stress, while when the stress was immobile it would be unstressed. Since stress is lost in Napnü, this surfaces as alternations in the quality of vowels in the suffixes. Words that had mobile stress became strong stems (since they get a strong thematic vowel), while words that had immobile stress became weak stems.

The speech registers of Tsuma have become highly lexicalized in Napnü, meaning we can speak of informal, formal, polite and foreign informal stems. What this means, is that the old speech register affixes are no longer used productively to mark the formality of a situation. Instead, they are now viewed by speakers as part of the lexeme, and even though the connection between related forms of different formality may be transparent to speakers, the forms are viewed as different words altogether. These new lexemes carry certain semantic connotations inherited from the Tsuma registers they derive from.

The reflexes of CT uma ‘to say’ are good examples of this. The unmarked form umë (i.e. domestic informal form) has become a colloquial word for ‘to speak’, i.e. ‘to chatter’ or ‘to have a chat’. The domestic formal form kumë has become the new default word for ‘to say; to speak’, and the domestic polite form numë is now a verb meaning ‘to discuss; to evaluate, to debate’.

The other foreign registers have almost no descendents. This is likely because the old foreign formal register was completely supplanted with the domestic formal register. The foreign polite register was already exceedingly rare in Common Tsuma, and was for the most part only used in political meetings between different Tsuma tribes. Hence, it does not have any reflexes in Napnü.

The Napnü noun is inflected for five cases and two numbers. Noun phrases are marked for definiteness with a proclitic.

Napnü maintains five case distinctions: nominative, accusative, oblique, comitative and abessive. The Tsuma case system was rearranged such that the old accusative merged with the nominative, resulting in many Napnü nominatives deriving from Tsuma accusatives. To fill the gap, the old dative supplanted the old accusative to fill the gap. The case endings are represented in the table below.

Table 6: Case endings

U-stems | I-stems | Bare stems | |||

Strong | Weak | Strong | Weak | ||

ɴᴏᴍ | -i | -i | -i | -i | -Ø |

ᴀᴄᴄ | -uh | -ëh | -ih | -ïh | -h |

ᴏʙʟ | -ukhë | -ëkhë | -ikhë | -ïkhë | -khë |

ᴄᴏᴍ | -uvi | -ëvi | -ivi | -ïvi | -vi |

ᴀʙᴇ | -uvü | -ëvü | -ivü | -ïvü | -vü |

O- and E-stems are always marked with -i in the nominative. This ending derives from the CT accusative ending. The nominative is left unmarked in bare stems, but a small set of bare stems have a different stem in the nominative derived from CT metastasized accusative forms.

Weak bare stems consist of monosyllabic words. The vowel in the case ending will become strong in the oblique and abessive forms, since the ending would attract stress in CT. This is also the cause of the vowelalternations found in the other endings. The weak stems have weak vowels because the stress was fixed to an earlier syllable in the word, while strong stems have strong vowels because the first syllable of the ending used to be stressed.

As for how the case forms are used, they are used very much like how one would expect from their names. The nominative marks the subject of a verb, while the accusative marks the direct object. The oblique has a number of uses, but its prototypical use is as a prepositional case, meaning nouns are placed in this case before postpositions. In other cases, it is used in compound constructions to mark the modifier Noun. The comitative is used to mark

Nouns phrases are marked for definiteness with a proclitic. It has three allomorphs: qu- before consonant, qw- before /i/ and /ɨ/ and q- before other vowels. Since it comes before the whole noun phrase, it will be found on the relative particle awa (from Tsuma abwé ‘here’) when a head noun is modified by a relative phrase.

Plurality is marked with reduplication and dissimilation of the consonant in the reduplicated syllable. E.g. zak ‘hand’, razak ‘two hands’. This form derives from the old dual. The old collective prefix of Tsuma developed into a derivational prefix for abstract nouns, and the old plural became a greater plural marker. The rules of plural formation is shown in the table below.

Table 7: Dissimilation of consonants in reduplication

Singular | Plural | Example |

#pV | #pV-v | panü - pavnü ‘languages’ |

#tV | #tV-s | tuvë - tüsvë ‘stones’ |

#kV | #kV-χ | këluk - këkhluk ‘sticks’ |

#qV | #qV-χ / #kV-χ | qayi - këhyi ‘noses’ |

#fV | #fV-w | foki - fëwki ‘sounds’ |

#sV | #sV-z | salë - sëzlë ‘friends’ |

#ʃV | #ʃV-j | shupü - shüypü ‘horses’ |

#χV | #χV-h | khuh - khühuh ‘rests’ |

#zV | #zV-ɾ | zak - zarak ‘hands’ |

#lV | #lV-w | lutï - lëwtï ‘boat water’ |

#jV | #ʃV-j | ya - shayë ‘lizards’ |

#wV | #wV-v | wisën - wivsën ‘cape’ |

The main pattern is that the second consonant is ‘softened’ in some respect. Sometimes this is done by changing the manner of articulation (i.e. from stop to fricative), sometimes by changing the voicing (i.e. from voiceless to voiced), and sometimes by changing the place of articulation (i.e. from uvular to pharyngeal). Note that the semi-vowel /j/ reverse the order and becomes fortified to /ʃ/.

From a synchronic point of view, one may very well analyze this as infixation, since syncope and vowel reduction often obscures the connection between the singular and plural forms so much. This is generally what I’ve done in my glossing, since it’s kind of difficult to segment these plural forms sometimes.

The evidential system of Tsuma was transformed into a new mood system, where the old direct evidential became the realis mood, while the old inferred and referred evidentials merged into a new irrealis mood. The language also marks both the subject and object with person prefixes. The aspectual distinctions have been retained well, but the prospective was absorbed by the inchoative aspect.

Napnü has two moods: realis and irrealis. The indicative is mainly used to mark the main verb of a sentence, while the subjunctive typically marks subordinated verbs.

There are five ways of conjugating verbs based on the stem type, which is complicated further by the vowel alternations that occur within stems. This system is parallel to the noun declentions.

Table 8: Verb conjugations

Verb Declensions | Strong U-stems | Weak U-stems | Strong I-stems | Weak I-stems | Bare stems | |

Imperfective | -Ø | |||||

Perfective | -ü | -wë | -ü | -wï | <w> | |

Inchoative | -ëm | -um | -ïm | -im | -m | |

Imperfective | -ëna | -ïna | -na | |||

Perfective | -üna | -wëna | -üna | -wïna | <w>-na | |

Inchoative | -ëma | -ïma | -ma | |||

There are five converb suffixes that are used to subordinate verbs. These are the imperfective, perfective, additive, purposive and negative/abessive converbs. The suffixes use the derivational verb stem, i.e. the same stem pattern as the passive and the causative.

Table 9: Converb suffixes

Converb | Suffix | English Equivalent |

Imperfective | -kë | ‘While’, ‘when’, ‘if’, ‘because’, ‘by means of’ |

Perfective | -nu | ‘After’, ‘having’ |

Additive | -shï | ‘Also’, ‘in addition to’, ‘along with’ |

Purposive | -h | ‘In order to’, ‘for the purpose of’ |

Negative | -shü | ‘‘Unless’, ‘if not’, ‘except’ |

Tsuma originally had a distinct causative converb, used specifically for senses such as ‘because’ and ‘by means of’. This form collapsed with the imperfective through regular sound change, but its meanings can still be conveyed with the imperfective form.

The negative converbs original function was as an abessive converb (meaning ‘without’ or ‘lacking’), but it has been generalized such that it is the primary negation strategy in the language. This is discussed in section 3.3.4.2. When it is used like a typical converb, it functions as an abessive converb

Various modal constructions are formed by combining the copula ravü with converbs. When the purposive converb is combined with the copula, it can convey an abilitative or permittative sense (see sentence (1)). When combined with the imperfective converb, it conveys a desiderative or necessitative sense (see sentence (2)).

(1) | Irvü hakhë hinlih | ||

i-ravü | hakhë | kh<in>ëli-h | |

1sɢ-be | 2sɢ.ᴏʙʟ | <1sɢ>help-ᴘʀᴘ.ᴄᴠʙ | |

‘I can help you’ (LIT. ‘I exist for my helping of you’) | |||

(2) | Irvü hakhë hinlikë | ||

i-ravü | hakhë | kh<in>ëli-kë | |

1sɢ-be | 2sɢ.ᴏʙʟ | <1sɢ>help-ɴᴘғᴠ.ᴄᴠʙ | |

‘I must/need to help you’ (LIT. ‘I exist because of my helping of you’) | |||

Napnü’s main strategy for negating verbs is to use the negative converb with the copula.

(3) | Irvü hakhë hinlishü | ||

i-ravü | hakhë | kh<it>ëli-shü | |

1sɢ-be | 2sɢ.ᴏʙʟ | <2sɢ>help-ɴᴇɢ.ᴄᴠʙ | |

‘I cannot help you’ | |||

Napnü verbs have separate forms of the root with a different vowel pattern, used to derive new verb stems. This is done by appending a derivational suffix after this special form. The passive form is distinct in its irrealis forms, in that it derives from the old reported evidential forms and not the inferred forms.

Table: Verb Derivations

Passive | Causative | |

ʀᴇᴀʟ.ɴᴘғᴠ | -ka | -shë |

ʀᴇᴀʟ.ᴘғᴠ | -kwa | -shfü |

ʀᴇᴀʟ.ɪɴᴄʜ | -kwam | -shfum |

ɪʀʀ.ɴᴘғᴠ | -karü, -krü | -shërü, -shrü |

ɪʀʀ.ᴘғᴠ | -kwarü | -shfürü |

ɪʀʀ.ɪɴᴄʜ | -kwamü | -shfümü |

This section goes over the person forms, demonstratives and time adverbials of Napnü. The section is therefore aptly named deixis.

Napnü innovated many different person forms for different purposes. There are two sets of prefixes used for argument indexing on verbs: one for the arguments of transitive verbs, and one for the subject of intransitive verbs. These act as cross-indexes, meaning they can occur with a conominal (i.e. an NP with the same referent). In addition, there are free or unbound person forms which are used for emphasis, which are inflected for case. Lastly, there is a set of nominal person prefixes which are used for possession and marking person on converbs.

The prefixes used on transitive verbs are shown below. The subject and object are encoded in one prefix.

Table 10: Argument prefixes

1sɢ.ᴏʙᴊ | 2sɢ.ᴏʙᴊ | 3sɢ.ᴏʙᴊ | 1ᴘʟ.ᴏʙᴊ | 2ᴘʟ.ᴏʙᴊ | 3ᴘʟ.ᴏʙᴊ | |

1sɢ.sᴜʙᴊ | --- | nji- | mi- | inne- | inwe- | inri- |

2sɢ.sᴜʙᴊ | hinja- | --- | fi- | hëni- | fe- | hëri- |

3sɢ.sᴜʙᴊ | winja- | we- | tiri- | one- | o- | ori- |

1ᴘʟ.sᴜʙᴊ | nanja- | ne- | ni- | --- | no- | nari- |

2ᴘʟ.sᴜʙᴊ | wanja- | we- | wi- | wane- | --- | wari- |

3ᴘʟ.sᴜʙᴊ | rinja- | re- | ri- | rine- | ro- | rirtu- |

STHe forms tiri- and rirtu- were originally dual forms. The old 3sg subject/3sg object prefix was wi-, which was identical to the 2pl subject/3sg object form. To reestablish the distinction, the 3du subject/3sg object prefix took its place. A similar thing happened with rirtu- which replaced older riri-, probably to make it more distinct from ri- since the forms could get difficult to distinguish in rapid speech.

Personal possession is marked with a set of person prefixes which modify nouns. These prefixes are also conveniently used on converbs to signal the subject, in which case they function as gramm-indexes since they cannot occur with a conominal.

Table 11: Nominal person prefixes

Singular | Plural | |||

#V | #C | #V | #C | |

1ᴘ | n- | <(i)n> | n- | n(a)- |

2ᴘ | h- | h(a)- | w- | w(a)- |

3ᴘ | t- | <it> | r- | r(i)- |

This set of prefixes is mostly used for kinship terms and nouns with proximal human referents. In other terms, they are used when the referent is closer to the speaker. When the human referent is further away, an oblique construction with an unbound person form is generally preferred (see section 4.3.).

Napnü has a set of free person forms which can co-occur with the argument indexes. Their purpose is to give extra emphasis to a particular referent or to make it more prominent in the sentence.

Table 12: Free person forms

ɴᴏᴍ | ᴀᴄᴄ | ᴏʙʟ | ᴄᴏᴍ | ᴀʙᴇss | |

1sɢ | inja | njah | njakhë | njavi | njavü |

2sɢ | hayi | hayih | hakhë | havi | havü |

3sɢ | uyi | uyih | ukhë | uvi | uvü |

1ᴘʟ | nayi | nayih | nakhë | navi | navü |

2ᴘʟ | wayi | wayih | wakhë | wavi | wavü |

3ᴘʟ | ri | rih | rikhë | rivi | rivü |

All of these forms except the 3rd person plural are derived from Tsuma accusatives. The new accusative forms are also derived from the accusative, but the new accusative ending -h has been added. This likely happened to reintroduce an accusative marker, since the old accusative now is largely associated with the new nominative.

Napnü inherits the expanded demonstratives of CT. The regular forms were mostly lost, with the exception of the dependent form ku, which became the definite proclitic q(w)-/qa-. The demonstratives are shown in the table below. As the table illustrates, the forms are clitisized and will lose their vowel when the following word begins in a consonant cluster.

Table 13: Demonstratives

Animate | Inanimate | |

ᴘʀᴏx | qwak(i)= | wïkh(u)= |

ᴅɪsᴛ | qwas(ë)= |

Napnü has 6 postpositions derived from Tsuma nouns and verbs. These are uk ‘on, on top of’, ma ‘in, inside’, il ‘from’, za ‘to, towards’, la ‘after, behind’ and mu ‘before, in front of’. When a postposition is used, the noun is placed in the oblique case. It is common in dialects clitisize postpositions onto nouns, e.g. qwërkhë ma ‘inside the room’ > qwrkh’ma in Northern Napnü

Table 14: Postpositions

Postposition | English |

uk | ‘On (top of), above’ |

ma | ‘In, inside’ |

il | ‘From, (out) of’ |

za | ‘To, towards’ |

la | ‘After, behind’ |

mu | ‘Before, in front of’ |

The basic word order of Napnü is VSO. This is different from Tsuma, which was SOV. The shift occurred mainly due to the innovation of person prefixes, which were derived from Tsuma free person forms (simply referred to as pronouns in the Tsuma reference document). When these person forms got prefixed to the verb, these were no longer considered independent arguments and were instead reanalysed as cross-indexes (i.e. the NPs that the person forms point to are made optional). This, in essence, made the language mostly verb-initial. This eventually solidified into a VSO-system, though other word orders are also possible.

A maximal noun phrase follow this template:

Noun Phrase | |||

(Determiner) | (NP-modifier) | Noun | (Relative Clause) |

Relative clauses are subordinated clauses that modify nouns. In Napnü, these come after the noun and are introduced by the relativizer awa (from Tsuma abwé ‘here’).

NP-modifiers are a way to modify NPs to express adjectival or possessive meanings. The main way is to put unconjugated intransitive verbs before a noun. In this position, the verb functions as a NP-modifier.

(4) | Qati ïmvü. | |

q=ati | ïmvü | |

ᴅᴇғ=be.funny | cat.ɴᴏᴍ | |

“The funny cat.” | ||

Nouns can also act as NP-modifiers. When this is done, the noun is placed in its oblique form before the head noun. This is somewhat similar to how construct phrases work in semitic languages.

(5) | Qunjwëkhë panü | |

qu=njawë-khë | panü | |

ᴅᴇғ=nation-ᴏʙʟ | language | |

“The national language.” | ||

When the NP refers to a carried item, it is placed in the comitative case. This developed from older uses of these cases as markers of alienable and inalienable possession in possessive constructions. In Tsuma, the comitative was used for alienable items, while the locative was used for inalienable items. Later, the inalienable construction broadened, resulting in the oblique being used in most cases, while the comitative got restricted in use.

A maximal verb phrase follows this template:

Verb Phrase | ||||

(Adverbial) | Verb | (Subject) | (Direct Object) | (Oblique) |

However, adverbs can also come at the end of the phrase in colloquial language.

Certan TAM-distinctions and valency-changing operations are carried out with auxiliary verbs. Many of these auxiliaries require the verb to be in a nominalized form, either a converb or a simple verbal noun.

Dative use of the accusative

Nishwë quhimya qwas ati ïmvuh. | |||

ni-she-wë | qu=himya | qwams=ati | ïmvu-h |

1sɢ.sᴜʙᴊ.3sɢ.ᴏʙᴊ-give-ᴘsᴛ | ᴅᴇғ=fish.ɴᴏᴍ | ᴅɪsᴛ.ᴀɴɪᴍ=funny | cat-ᴀᴄᴄ |

“I gave the fish to that funny cat over there.” | |||

Unexpectedly, the direct object of the verb she ‘to give’ is marked in the nominative and the indirect object with the accusative. This is because the verb she retains the “older” uses of the case forms as they were before the case system was resorted. Essentially, the old nominative and accusative merged, and the old dative became the new accusative. In the argument structure of this particular verb, the case use is fosilized in a way.

Negation

Imyinu ërkhë za, irvü ïmvukhë ëvshü

i-mayi-nu arë-khë za, irvü ïmvü-khë ëvashü

my-going-CVB.PFV home-OBL to, I.am.in the=cat-OBL seeing-CVB.NEG

“I couldn’t see the cat when I got home.”

Mythos

upnuka farës nümak awa winmë quvisyerkhë yëpyü awa wipu Üluk khüshkë a fëykë

[ubnugáː faɾəs nʉmag awa winmə quvisjɛɾχə jəbjʉ awa wibu ulúːk χʉʃkə a fəjgə]

u-pënu-ka farës nümak awa wi-numë qu=fisyerü-khë yëpyü awa wi-ëpu Uluk khüshu-kë a fëyu-kë

3sɢ-known-ᴘᴀss.ʀᴇᴀʟ.ɴᴘғᴠ old story.ɴᴏᴍ ʀᴇʟ 3sɢ.sᴜʙᴊ.3sɢ.ᴏʙᴊ-discuss.ʀᴇᴀʟ.ɴᴘғᴠ ᴅᴇғ=world-ᴏʙʟ creation.ɴᴏᴍ ʀᴇʟ 3sɢ.sᴜʙᴊ.3sɢ.ᴏʙᴊ-do<ʀᴇᴀʟ.ᴘғᴠ> U. sleep-ᴄɴᴠ.ɴᴘғᴠ and dream-ᴄɴᴠ.ɴᴘғᴠ

“An old myth is known, which tells of Uluk, the great Frog, who created the world in his dreaming slumber.”

(LIT. ‘An old story is known which discusses the creation of the world which Uluk did while sleeping and dreaming.’)

Comparison between CT, Pyuna and Napnü

CT | Pówu ánapyú ígaleko, okyíli ánapú okkuho mádzat. Dádákoho okyíliho kolok, ga okkuho wo ogyi máz. Nabígáxayi o? |

Pyuna | Pó áhonapú i égalä, ga gâga ánapú ho howa. Gâga ani dáko ho kolokä, ga okku ho wo ogi márä. Ná bígáxayi o? |

Napnü | umyikë pavü qwampukhë il, umzët oshli ukhë uk. Këluk quzrakkhë oshlikhë ma, a ori mar oqkhë uk. Naviryëyi? |

Differences: