Tsuma Reference Document 2024

Tsuma Reference Document

Fall 2024

Contents

2.3. Phonotactics & Prosody 13

2.5. Phonological Processes 16

2.5.1.1. Prefixal metathesis 16

2.5.1.2. Suffixal metathesis 16

3.4.5.1. Domestic registers 30

3.4.6.1. The imperfective converb 31

3.4.6.2. The perfective converb 31

3.4.6.3. The additive converb 31

3.4.6.4. The causative converb 32

3.4.6.5. The purposive converb 32

3.4.6.6. The counterfactual converb 32

3.5. Derivational morphology 33

6.1.3. Origin of metathesis 44

6.1.4. Origin of consonant mutation 45

6.2.3. Pronouns & demonstratives 45

6.3.1 Subject-Verb Agreement 46

7.1.3. Important insight from a frog 52

Tsuma is a conlang I began working on during the winter of 2021, which I’ve been working on inconsistently since. I started working on a second draft in late spring 2022, and I continued developing the language continuously till the end of that year. The first draft was very different from the later drafts, but some key features are still present: a verbal system with emphasis on evidentiality, a head-final syntax and a morphology with some infixation. All of this is of course in the framework of naturalism, the goal being that the language should follow the same principles as naturally occurring human languages.

The Tsuma peoples do not have any names for themselves. They see themselves as simply ‘the people’ or ‘the tribes’, and all other names for them are exonyms given to them by other cultures, these being entirely unknown by them. They are referred to as the Tsuma in this document and elsewhere, as this is my personal name for the language, but the name is not used by the speakers in the conworld. ‘Tsuma’ is simply the collective form of the noun uma ‘speech’ or ‘mouth’, and so the name actually means ‘all (of our) speech’. One way this word form would occur naturally is in the phrase tsuma nyéweho, meaning ‘the speech of all tribes’.

As for the peoples themselves, their lifestyle varies depending on region. They most commonly live as hunter-gatherers, but a sizable population in the southern regions rely on fishing. There are some permanent settlements in these areas, but the vast majority of the Tsuma peoples are nomadic, moving through the tropical forests while not staying in the same spot for too long. They are culturally divided into different tribes, but these tribes have very frequent contact with each other, even going so far as to forming large intertribal alliances.

Tsuma can be summarized as a head-final nominative-accusative language with fusional tendencies. Verbs are marked for aspect, evidentiality and register, while nouns have different forms for singular, plural, dual and collective. There are eight cases, which historically evolved from postpositions.

Tsuma can be said to belong to a sprachbund with some of its neighbouring languages, particularly the Pakesia language. They both share SOV word order and nominative-accusative alignment despite most neighbouring languages being ergative. This has led many in-world linguists to believe Tsuma has a genetic relationship to the Wjusan language family (the family to which Pakesia belongs); however this theory is incorrect, and in reality the similarities between Pakesia and Tsuma have most likely arisen through intensive language contact. What is more likely is that Tsuma is a separate language family without any currently existing relatives. There are however more closely related variants which are too distinct to be called dialects of common Tsuma, which must have split off before most of the developments from Old Tsuma took place.

Even though trade is not as prevalent as in many of the other neighboring language communities, the Tsuma do engage in trade with some outside cultures, primarily Ocogian-speaking peoples in the north and Pakesia-speaking peoples in the south. The contact is particularly strong with the speakers of Pakesia where there is a shared fishing culture. In areas of frequent contact, bilingualism is quite common, and loans are usually adopted here first before they spread northward to the rest of the population.

Pakesia is a language spoken on the islands south of the Tsuma communities. Typologically, it resembles Tsuma in many areas, although with much fewer agglutinative tendencies and with more complicated inflection. Its basic word order is also SOV, and noun phrases are marked for case with obligatory postpositions. Pakesia is also almost entirely head-final. The syllable structure of Pakesia is also very similar, being entirely CV and only allowing at most two consecutive vowels, although their phonemic inventories differ. As such, loan-words from Tsuma take a considerably altered form in Pakesia. Generally, Tsuma has more sounds than Pakesia and this also means that the Pakesia adaptation of the Tsuma writing system has many more symbols than needed.

Verb morphology comes in three aspects, two moods and three tenses. Evidentiality is not obligatorily marked like Tsuma and thus stands out considerably in this aspect too. Nevertheless, these two languages are in close contact especially in fishing communities, but this is mostly seen in shared vocabulary.

Ocogian is a language spoken to the north, and as such it is the northern dialects of Tsuma which most often come into contact with Ocogian. The language is very phonologically complex, is predominantly head-marking, and has a polysynthetic morphology where the form of the roots and morphemes are difficult to recognize in different conditions. Hence, individual roots and morphemes essentially never get borrowed into Tsuma. Instead, phrases themselves are what usually gets borrowed. Some other notable features are articles and incorporated adverbs.

The Tsuma are not particularly interested in the affairs of the larger civilizations that geographically surround them. Nevertheless, their engagement in trade with various peoples makes them connected to the other inhabitants of the world.

The most prominent civilization in the world at large are the Liqak, who reside beyond the mountains to the east of Tsuma. The Liqak are known for their frequent engagement in wars and territorial disputes. Even though the mountains provide some protection from these affairs, there are certain passages that allow open travel, creating a narrow point of contact between the eastern Tsuma tribes and the Northern Liqak.

Other prominent civilizations are the Obêgoky, who reside in the mountainous areas North of where the Tsuma reside. The Obêgoky are a mostly peaceful people, with a highly organized society. They are the most important trade partners of the Tsuma.

Image 1: Rough map of the world

ABESS | Abessive |

ABL | Ablative |

ACC | Accusative |

ADD | Additive |

B-stm. | Bare stem |

CAUS | Causative, Causal |

CNTF | Counterfactual |

COL | Collective |

COM | Comitative |

CP | Classical Pakesia |

CT | Common Tsuma |

CVB | Converb |

DAT | Dative |

DIR | Direct evidential |

DU | Dual |

E-stm. | E-stem |

INCH | Inchoative aspect |

INFR | Inferred evidential |

INS | Instrumental |

LOC | Locative |

NOM | Nominative |

NPVF | Imperfective aspect |

NZ | Nominalizer |

O-stm. | O-stem |

OC | Ocogian |

OT | Old Tsuma |

PFV | Perfective aspect |

PL | Plural |

PROS | Prospective aspect |

PRP | Purposive |

REFL | Reflexive |

RPT | Reported evidential |

The consonants are given in Table 1, while the vowels are given in Table 2. These charts are based on a pan-dialectal analysis.

Table 1: The consonant inventory

Labial | Coronal | Dorsal | Glottal | ||

Plain | Lateral | ||||

Nasal | m | n | |||

Stop | p, b | t, d | k, g | ʔ | |

Affricate | ts, dz | tɬ, dɮ | |||

Fricative | (f) | s, z | h | ||

Sonorant | w | l | j | ||

Table 2: The vowel inventory

Front | Back | |

High | i, iː | u, uː |

Mid | e, eː | o, oː |

Low | a, aː | |

The consonants are generally realized as one would expect from the chart.

The consonants are one area where the dialects differ the most. The distinctions shown in Table 1 are for the most part present in all dialects.

.

The vowels do not vary much depending on dialect, being almost identical for all speakers. Tsuma has the typical five vowel system with contrastive length. I cannot think of anything interesting to say about it.

Tsuma can be said to have two main syllable templates; ((ʔ)C(w/j))V for non-final syllables, and ((ʔ)C(w/j))V(C(j)) for final syllables. Only the continuants /s, z, l, j, w, m, n/ can be preceded by /ʔ/. The sonorant /w/ cannot follow /ts, dz, tɬ, dɮ, h, j/, and the sonorant /j/ cannot follow /ts, dz, tɬ, dɮ, h, w/. In the cases where such clusters should arise due to morphophonological processes, an /u/ is inserted before /w/ and an /i/ before /j/. Plosives, affricates and sibilants may sometimes be geminated after vowels, however most of the possible geminates are not very frequent. All consonants, with the exception of /g, ʔ, h/, are permitted word-finally. The clusters /kj/ and /gj/ are the only ones that also occur word-finally. All possible consonant clusters are schematicised in Table 3.

Table 3: Possible consonant combinations

m | n | p | b | t | d | k | g | x | ts | dz | tl | dl | f | s | z | h | w | l | y | |

m | mw | my | ||||||||||||||||||

n | nw | ny | ||||||||||||||||||

p | pp | pw | py | |||||||||||||||||

b | bb | bw | by | |||||||||||||||||

t | tt | tw | ty | |||||||||||||||||

d | dd | dw | dy | |||||||||||||||||

k | kk | kw | ky | |||||||||||||||||

g | gg | gw | gy | |||||||||||||||||

x | xm | xn | xx | xs | xz | xw | xl | xy | ||||||||||||

ts | tts | |||||||||||||||||||

dz | ddz | |||||||||||||||||||

tl | ttl | |||||||||||||||||||

dl | ddl | |||||||||||||||||||

f | fw | fy | ||||||||||||||||||

s | ss | sw | sy | |||||||||||||||||

z | zz | zw | zy | |||||||||||||||||

h | ||||||||||||||||||||

w | ||||||||||||||||||||

l | lw | ly | ||||||||||||||||||

y |

Different syllable types can be defined; a short open syllable is one where the vowel is short and there is no coda consonant; a short closed syllable is one where the vowel is short and there is a short coda consonant; a long open syllable is one where the vowel is long and there is no coda consonant; a long closed syllable is one where the vowel is short and the coda consonant is geminated; a heavy syllable is one where the vowel is long and there is a short coda consonant; and finally, an overlong syllable is one where there is both a long vowel and a geminate as coda.

Short open syllables: CV, ʔCV, V

Short closed syllables: CVC, ʔCVC, VC

Long open syllables: CVV, ʔCVV, VV

Long closed syllables: CVVC, ʔCVVC, VVC, CVCC, ʔCVCC, VCC

Overlong syllables: CVVCC, ʔCVVCC, VVCC

Most of the syllable types involving geminates are quite rare, with the overlong syllables being the least common ones. Importantly, whenever an onset consonant is followed by /w/ or /j/ in a cluster, these semi-vowels do not add to the syllable length.

Stress is determined by the syllable type; the longest one receives the stress, and whenever there are multiple longer syllables of the same type, the earliest one receives the stress. The stress lands on the penult if all the syllables of a word are of equal length.

Table 4: Examples of stress placement in some words.

Examples of stress placement | Example word | IPA | Gloss |

ˈCVCV | tuwa | [ˈtuβa] | shiny.stone |

CVˈCV: | legó | [ləˈgoː] | wait.DIR.IMP |

CVˈCVCV | lehabu | [ləˈha.bʊ] | shine-PROSP.RPT |

ˈCV:CVCV | dláhama | [ˈdɮaːha.ma] | wake.up-INCH.DIR |

CVˈCVC | kolok | [kɔˈlok] | stick |

ˈCV:CVC | yánat | [ˈjaːnat] | exist.DIR.IMP |

Long vowels are marked with an acute accent V́. The affricates /ts, dz, tɬ dɮ/ are written as <ts, dz, tl, dl>, the sonorant /j/ as <y> and the glottal stop /ʔ/ as <x>.

Loan words are typically adapted such that the stress placement is preserved. This may be done by lengthening the vowel or shortening a geminate. Certain consonants are often substituted for others. The uvular stop [q] is generally replaced with /ʔ/ in all dialects, while /f/ is only preserved in the dialects where contact with neighbouring languages frequent.

Tsuma has different phonological processes which come into play when affixes are added. The most active of these are metathesis, of which there are two types; prefixal and suffixal metathesis; and consonant mutation, of which there are five types; sibilant, labial, nasal, coronal and glottal mutation.

Metathesis is a recurring pattern in Tsuma morphophonology. The original cause of this has to do with Tsuma’s restrictive phonotactics. Elision and apocope caused more consonants to border each other, and this did not fare well with the CV-structure the language had developed at that time. The clusters were solved by metathesising their elements inside the word stem. Two types of metathesis can be identified: prefixal metathesis and suffixal metathesis.

Prefixal metathesis is most visible in the pronominal prefixes. Prefixes ending in a consonant (1-person in- and 3-person it-) are shoved behind the initial consonant of the root. This only happens when the root itself begins in a consonant. The rule does not apply to roots beginning in vowels, since no problematic cluster would arise from applying the prefixes to those.

Suffixal metathesis denotes a process whereby morphemes are realized inside the final syllable of word-stems, particularly bare stems (the process does not apply to o- and e-stems). The morphemes -y- (accusative case) and -w- (perfective aspect) are placed inside the final syllable, i.e. between the onset consonant and the vowel: CV# → R > CRV# (where R denotes /j, w/). However, because of Tsuma's restrictive phonotactics, this is often impossible without applying certain phonological rules, modifying the final syllable of the word-stem to fit the phonotactic constraints while maintaining distinctions. The following rules govern this:

CV# + -R → CRV#

Example words:

xópi + -y → xópyi

xidága + -w → xidágwa

dúwu + -w → dúwu

hékyá + -y → hékyiyá

CV# + -R → CRVV

Example words:

uma + -w → umwá

tuwa + -y → tuwiyá[1]

kayi + -y → kayí

CV# + -R → CVRV[2]

Example words:

kuwá + -w → kuwáwu

ha + -y → hayi

CV# + -R → CV [quality of V copies R]

sáya + -y → sáyi

mahéwo + -w → mahéwu

When the final syllable onset is occupied by the same semi-vowel as found the ending, the R is deleted, as exemplified by the third example under rule I. It may still lengthen the vowel in accordance with rule II, as shown in the third example. Rule III is applied when distinguishing forms is particularly important. For the accusative, this includes pronouns, agentive nouns or nouns denoting entities perceived as having a lot of agency. There are fewer tendencies in verbs, where one can chose to underspecify if the context allows it. In many cases, either Rule I or Rule IV can be applied. In such cases, Rule IV is preferred.[a]

The rules of the system are largely due to the language’s stress rules, phonotactics, and need to maintain certain grammatical distinctions. The historical background of suffixal metathesis is explained in section 6.1.3.

The initial consonant of a root may change when various affixes are added. Some prefixes trigger all the possible kinds of mutation, while some only trigger one or a few. There are five types of mutation: sibilant mutation, labial mutation, nasal mutation, coronal mutation and glottal mutation. Examples of all the above are presented in Table 5.

Mutation in Tsuma is different from mutation in other languages in that it is a completely unproductive system. It reflects the various outcomes of old clusters and phonemes which have later merged. (This is further explained in section 6.1.3). In other words, using nasal mutation as an example, /n/ turning into /g/ only happens for some words with initial /n-/, not all. Whether a word undergoes initial mutation is indicated in a dictionary.

Table 5: Overview of the various affixes that trigger mutations. Note that the columns ‘Pronominals’ and ‘Honorifics’ here refer solely to prefixes and not infixes, even though both of those categories have infixes. The infixes of both of these categories are conveniently grouped together in the column named ‘Infixes’.

Initial | Mutated | Type | Triggers | ||||||

Infixes | Pronominals | Honorific | Refl. | Aug. & Dim. | Pl. & Col. | Dual | |||

s-, z- | -sː-, -zː- | Sibilant | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

p-, b- | -l- | Labial | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

n- | -g- | Nasal | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

t-, d- | -p-, -b- | Coronal | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

h-, ky- | -j-, -w- | Glottal | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes[3] |

Sibilant mutation geminates initial /s/ and /z/ to /sː/ and /zː/. It is triggered by the honorific and pronominal prefixes. It is not triggered by infixes as this is not phonotactically possible.

Labial mutation changes the labials /p/ and /b/ to the lateral /l/. It is triggered by the pronominal and honorific prefixes and infixes, as well as the reflexive prefix.

Nasal mutation turns /n/ into /g/. It is triggered by the pronominal and honorific prefixes, the reflexive prefix, and the augmentative and diminutive markers.

Coronal mutation turns /t/ and /d/ into the labial stops /p/ and /b/. It is triggered by the pronominal prefixes, the reflexive, the augmentative, the diminutive, the plural and the collective.

Glottal mutation turns /h/ into /w/ before back vowels (including /a/) and /j/ before front vowels. It can also turn the cluster /kj/ into /j/. All the affixes that trigger coronal mutation also trigger glottal mutation. The mutation /h/ to /j/ can also be triggered by the dual.[b][c][d]

Nouns and verbs are divided into three stems: e-stems, o-stems and bare stems. E- and o-stems are words which historically ended in short /e/ and /o/ respectively, while bare stems are words which still end in vowels. In the former two classes, the historical vowels reappear when various suffixes are added.

Nouns are inflected for 4 numbers: singular, dual, plural and collective; and for eight cases: nominative, accusative, dative, locative, ablative, comitative, instrumental and abessive. Additionally, pronominal markers can be prefixed to nouns to mark possession. This is in stark contrast to Old Tsuma, which had no morphological marking on nouns.

All of these case endings derive from postpositions in Old Tsuma. Their origins are further discussed in section 5.2.1. The case endings are displayed in Table 6.

Table 6: The case endings

Bare stems | E-stems | O-stems | |

Nominative | -Ø | -Ø | -Ø |

Accusative | -(i)y-, -yi | -i | -i |

Western accusative | -gy | -egy | -ogy |

Dative | -tl | -etl | -otl |

Locative | -ho | -eho | -oho |

Ablative | -nu | -enu | -onu |

Comitative | -bye | -ebye | -obye |

Instrumental | -ga | -ega | -oga |

Abessive | -byu | -ebyu | -obyu |

There are four numbers: singular, plural, dual and collective. The singular is unmarked, while the plural is formed with the prefix an(i)-. The dual is formed through partial reduplication, while the collective is marked with the prefix ts(i)-. The number markers are shown in Table 7. The singular is often used as an underspecified form or paucal form, meaning either one or some of something. The collective is also often used derivationally to create nouns for general concepts, for instance tsidotl ‘humanity’ from dotl ‘human’.

Table 7: The number markers

#C | #V | Example | Gloss | |

Singular | Ø- | Ø- | dák | hand |

Plural | ani- | an- | anidák | PL-hand |

Dual | Ø~ | Ø~ | dádák | DU~hand |

Collective | tsi- | ts- | tsidák | COL-hand |

Reduplication is done by repeating the first CV or VC of a word. As is the case in Table 7, a word like dák will become dádák in its reduplicated form. Words with an initial syllable of the form V, like agya ‘home’, will bring the onset consonant of the second syllable along in the reduplicated syllable, hence agyagya in the reduplicated form. In the cases where a word has consecutive vowels (only really found in loan words), a glottal stop is inserted between the reduplicated syllable and the initial syllable of the root, hence aufa ‘handyman’ > axaufa.

The number markers can go together with the pronominal affixes. The pronominal affixes are added closer to the root and the number markers are added after, as seen in Figure 1. The exception is the dual, where the reduplication happens before the pronominal affix is added, as seen in Figure 2.

Figure 1: morphological tree of anihapágu ‘your knives’.

Figure 2: morphological tree of hapápágu ‘your pair of knives’

Modality in Tsuma is expressed using modal nouns. These nouns may be translated or glossed as ‘obligation’, ‘wish’ or ‘ability’, but they serve the same function as modal auxiliary verbs in languages like English. These nouns are rarely, if ever, used in other contexts. Being nouns means they can take pronominal prefixes, which are then typically followed by verbal predicates. For more information on predicates, see section 4.2.

(1) | xinéku | woyi | enwa |

x<in>éku | wo-y | enwa | |

<1SG>wish | 3SG-ACC | know | |

‘I want to know’ | |||

In sentence (1), the modal noun xéku ‘wish’ is used. Examples of other modal nouns are ikuz ‘need, obligation’ and yána ‘ability’.

Pronouns in Tsuma are words which can substitute a noun or a noun phrase. This section covers personal pronouns, pronominal affixes and demonstratives.

The basic set of pronouns distinguishes between the same numbers as nouns. There is also a neutral/polite-distinction between the 1-person singular pronouns ina and sulu. The polite form is used in the same context as the polite registers, which are described in section 3.4.4. The personal pronouns are shown in Table 8.

Table 8: Personal pronouns

Singular | Plural | Dual | Collective | ||

1-person | Neutral | ina | ná | initi | xná |

Polite | sulu | ||||

2-person | ha | wá | hagú | xwá | |

3-person | wo, iti | gyí | tigú | xugyí | |

The 3-person singular pronoun has an alternative variant iti, which is most commonly found in eastern dialects. It is the more etymological variant, as wo descends from an old demonstrative, while iti descends from Old Tsuma *ite. The dual and collective forms are not derived the same way as in nouns. The 2- and 3- person dual forms are contractions of the singular forms and the numeral igú, and the collective forms are contractions of the plural forms and the intransitive verb xul ‘to be whole’.

Pronominal affixes are used to mark pronominal possession in Tsuma. Here, ‘affix’ is used since prefixes and infixes behave differently. These differ as to what types of metathesis they trigger, but underlyingly the infixes are metathesized prefixes.

Table 9: The pronominal affixes

Singular | Plural | |||

#C | #V | #C | #V | |

1-person | -in- | in- | na- | n- |

2-person | ha- | h- | wa- | w- |

3-person | -it- | it- | gyi- | gy- |

The prefixes can trigger all forms of consonant mutation, while the infixes only trigger labial mutation (see the table in section 2.5.2). This has to do with the order of historical changes in the transition from Old Tsuma to Common Tsuma, which is described in section 5.3.

There are two sets of demonstratives. The regular forms are either independent, functioning essentially like nouns, or dependent, only ever occurring attributively. The independent forms can never act as attributive demonstratives, and the dependent form can never act as an independent demonstrative. The expanded forms can be both independent and dependent, but also have a proximal/distal-distinction. The demonstratives are shown in Table 10.

Table 10: The demonstrative pronouns.

Regular forms | Inanimate | Animate |

Independent | xwehu | kwám |

Dependent | ku | ku |

Expanded forms | Inanimate | Animate |

Proximal | xwehuki | xwehuki, kwámoki |

Distal | xwehusa | xwehusa, kwámosa |

The expanded forms are used similarly to how one would use ‘right here’ or ‘over there’ when talking about an object in English. They may for instance be used to differentiate between things that are in different locations, or to reference something nearby in contrast to something further away. Note also how the animate expanded forms can make use of both xwehu- and kwám-. This is due to historical reasons, like kwám being a relatively new form. For further discussion on the development of demonstrative pronouns, see section 5.2.3.

The verb is the most heavily inflected part of speech in Tsuma. Verbs are conjugated for 4 aspects; imperfective, perfective, inchoative and prospective; and 3 evidential categories; direct, inferred, and reported. Reflexive, causative and nominalizing affixes also exist.

Table 11: Verb conjugation

Direct (DIR) | Inferred (INFR) | Reported (RPT) | |||||||

B-stm. | O-stm. | E-stm. | B-stm. | O-stm. | E-stm. | B-stm. | O-stm. | E-stm. | |

NPFV | -Ø | -Ø | -Ø | -né | -oné | -ené | -gu | -ogu | -egu |

PFV | -w- | -wo, -wó | -we, -wé | -w-né | -woné | -wené | -w-gu | -wogu | -wegu |

INCH | -ma | -oma | -ema | -mé | -omé | -emé | -mu | -omu | -emu |

PROS | -ba | -oba | -eba | -bé | -obé | -ebé | -bu | -obu | -ebu |

As visualized in Table 11, the perfective is characterized by -w- (while leaving the imperfective unmarked), the inchoative by -m-, and the prospective by -b-. The inferred is characterized by a final -é, the reported by a final -u, while the direct has no marking.

Note that for bare stems, the inferred and reported suffixes are always preceded by a metathesized -w- in the perfective. This involves suffixal metathesis (see section 2.5.1.2.) and often also vowel insertion (see section 2.3.). In the direct perfective, the suffix of o- and e-stems get a lengthened vowel whenever the word-stem consists of only short open syllables E.g., the verb xul ‘to be whole’ is xulwó in the direct perfective. This follows rule II in section 2.5.1.2.

Tsuma is a tenseless language in the sense that it does not have any obligatory marking for grammatical tense. It instead marks for aspect, showing how an action extends over time, but with no reference to place in time, be it past, present, future, etc. Reference time can be conveyed using time adverbs or context.

The distinction between the inchoative and prospective is that the former focuses on changes from one state to another with focus on the transition itself, while the prospective instead denotes that a state is going to happen after the time of reference.

There are three evidential categories: direct, inferred, and reported. These are mandatorily marked on every verb in Tsuma. Using the wrong evidential can have the same social consequences as being caught lying or misrepresenting information in English.

Negation is marked with the clitic =(a)du (/a/ inserted for e- and o-stems). Its usage is quite broad, being applicable to most parts of speech; most commonly verbs where it is added after all the inflection, but also adverbs and even pronouns. There is also an older negation particle oz, which is only used in some frozen expressions, as well as more obscure constructions used in certain dialects.

Reflexive verbs can be formed by prefixing ba(s)- to the verb, and causatives can be formed by suffixing -lí to the root of the verb. These affixes are very productive, but there are also less productive affixes. In the past -t was used to form passives, and iteratives could be formed by reduplicating the initial syllable of the verb, but these are not productive anymore. However, they are still commonly found as frozen endings on various verbs. These are quite numerous. Some examples are:

Old Tsuma *-to (-PASS)

Old Tsuma CV~CV (ITER~)

Verbs which used to be passive forms often assign different cases to their arguments. For instance, the verb mádzat ‘to sit requires that its patient be in the dative case. The verb negekki does not look like an iterative in Common Tsuma, but it was originally an iterative of nekki ‘to etch’. Originally the iterative form was used for etching out various communicative signs on trees, but as writing was introduced it started being used for the act of writing instead.

There are 6 speech registers, marked with honorific prefixes on verbs. These are divided into two categories, the domestic register and the foreign register; the former being when talking to people within one’s own tribe, and the latter being used when talking to people outside the tribe. Within these two categories is a three-way distinction between informal speech, formal speech and polite speech.

The informal domestic register is by far the most common one, as people usually talk the most with friends and family in their tribe. The foreign registers are generally rarer than the domestic ones, however the informal one is still quite common, as this is the register the southern Ula (a loan from Pakesia, roughly ‘fishing team’) use when talking to Pakesia fishers. The prefixes are shown in Table 12.

Table 12: The honorific prefixes

Domestic registers | Foreign regisers | |||

#C | #V | #C | #V | |

Informal | Ø- | Ø- | tlu- | tl- |

Formal | -uk- | uk- | -ux- | x- |

Polite | u- | un- | tu- | t- |

Speech register is marked on most verbs wherever possible, with the exception of verbs in relative clauses and converbs. These remain unmarked for register.

Tsuma uses converbs where English employs subordinators like ‘because’ and ‘while’. The converb suffixes derive a non-finite form of the verb which expresses adverbial subordination. This is the main way of forming subordinate clauses in Tsuma. The possible converb forms are imperfective, perfective, additive, causal, purposive, and counterfactual. Example sentences (2) to (7) only differ in the converb forms used, and serve to illustrate the different meanings expressed by them.

Formed with the suffixes -ko, -oko, -eko. It is used for actions coocuring with the event expressed by the main verb, like English ‘while’, ‘when’, or ‘as’. It also expresses conditionals, similar to English ‘if’.

(2) | himyá | obáko | wo | tiha | baxyepwigu |

him<y>a | obá-ko | 3SG | tiha | ba-xyepwi-gu | |

fish<ACC> | see-IPFV.CVB | they | happily | REFL-raise-NPFV.RPT | |

‘While seeing the fish, they happily stood up, allegedly’ | |||||

Formed with the suffixes -nu, -onu, -enu. It is used for actions which are completed when the event of the main verb is happening, like English ‘after’ or ‘having’.

(3) | himyá | obánu | wo | tiha | baxyepwigu |

him<y>a | obá-nu | 3SG | tiha | ba-xyepwi-gu | |

fish<ACC> | see-PFV.CVB | they | happily | REFL-raise-NPFV.RPT | |

‘Having seen the fish, they happily stood up, allegedly’ | |||||

Formed with the suffixes kye, -okye, ekye. It is used for expressing that the information is an extra addition, similar to English ‘also’, ‘along with’ or ‘in addition to’.

(4) | himyá | obákye | wo | tiha | baxyepwigu |

him<y>a | obá-kye | 3SG | tiha | ba-xyepwi-gu | |

fish<ACC> | see-ADD.CVB | they | happily | REFL-raise-NPFV.RPT | |

‘Along with seeing the fish, they happily stood up, allegedly’ | |||||

Formed with the suffixes -ka, -oka, -eka. It expresses the cause of an action, similar to English ‘because (of)’ or ‘by means of’

(5) | himyá | obáka | wo | tiha | baxyepwigu |

him<y>a | obá-ka | 3SG | tiha | ba-xyepwi-gu | |

fish<ACC> | see-CAU.CVB | they | happily | REFL-raise-NPFV.RPT | |

‘Because of (their) seeing the fish, they happily stood up, allegedly’ | |||||

Formed with the suffixes -tl, -otl, -etl. It expresses the purpose for why something is happening, similar to English ‘in order to’.

(6) | himyá | obátl | wo | tiha | baxyepwigu |

him<y>a | obá-tl | 3SG | tiha | ba-xyepwi-gu | |

fish<ACC> | see-PRP.CVB | they | happily | REFL-raise-NPFV.RPT | |

‘They happily stood up so they could see the fish, allegedly’ | |||||

Formed with the suffixes -kyu, -okyu, -ekyu. It expresses a state of affairs which cannot be the case if the event expressed in the main clause is to be true, similar to English ‘unless’ or ‘if not’.

(7) | himyá | obákyu | wo | tiha | baxyepwigu |

him<y>a | obá-kyu | 3SG | tiha | ba-xyepwi-gu | |

fish<ACC> | see-CNTF.CVB | they | happily | REFL-raise-NPFV.RPT | |

‘They might happily stand up unless (they) see the fish, allegedly’ | |||||

Tsuma has a wide array of derivational suffixes used to derive new content words, i.e. either nouns, verbs or adverbs.

Verbal nouns are derived with the suffix -k. Examples are umak ‘speech’ from uma ‘mouth; speech’, enwak ‘knowledge’ from enwa ‘know’, dláhak ‘awakening’ from dláha ‘to awaken’, etc.

Adverbs are an independent class in Tsuma, and there are many roots which only show up as adverbs. However, there are a variety of ways to derive adverbs from other word classes. The most common way is by using converb suffixes, as discussed in section 3.4.6. This only works for verbs, but it is also possible to derive adverbs from nouns by using cases, like the dative -tl. These are often fosilized to the point where they can only function as adverbs. Likewise, there is a set of adverbs ending in -o, which are originally locative nouns, e.g. gáno ‘still, not moving’ from gánoho ‘in stone’, tsixo ‘always’ a contraction of tsixiho ‘at all times’ and bíxo ‘often, generally’ a contraction of bíxiho ‘in greater time’.

There is one suffix which has the sole purpose of creating adverbs: -ku, from an old postposition kú in Old Tsuma. It can derive adverbs from both nouns and verbs. E.g. the adverb xuloku ‘fully’ is derived from the verb xul ‘to be whole’.

The verbalizing suffix -pu is used to turn nouns into verbs meaning ‘to act or do as N’. For instance, sámmapu ‘to be curious’ is derived from the noun sámma ‘bird’

The resultative suffix takes turns verbs into nouns meaning ‘result of doing V’. For instance, the resultative of tsébet ‘to vanish’ is tsébetoxu ‘dissapearence’, and the resultative of kyúda ‘to kill’ is kyúdaxu ‘cadaver’.

The suffix -gya can be used to turn words into nouns meaning ‘place of X’.

Agent nouns can be derived with the suffix -(x)ám.

Tsuma word order is verb-final, meaning the verb always has to be the final element of the sentence. The question particle o comes after it however. The arguments of the verb are not as strict in their ordering, though subject first is the most common and basic of the all combinations. Still, both direct objects and indirect objects can come first in the sentence, and their roles are not ambiguous because of their case marking. Adverbs most often come before the verb and after the direct object if there is one, but their placement is also relatively free.

Tsuma does not have a true copula. Predicates are usually placed right after the subject without any linking element. However, the comitative and abessive cannot act as independent predicates, and require the use of the verb xot ‘to accompany’. This verb is irregular, and all its forms are given in Table 8.

(8) | ná | agya-ho | |

1PL | home-LOC | ||

‘We are home’ | |||

(9) | sulu | Lígyak-enu | |

1SG.RESP | Liqak-ABL | ||

‘I am from Liqak’ | |||

(10) | ina | gáxayi-bye | xot |

1SG | father-COM | accompany | |

‘I am with my father’ | |||

In the scenario where one would want to express something equative, e.g. ‘I am a rock’, one would do so in this fashion, i.e. ina gán ‘1SG rock’. But to express your profession, you simply say what it is you do, e.g. wo peka ‘3SG help.DIR.IMP’ for ‘they are an assistant’.

Questions are formed with the particle o. The distinction between yes/no-questions and content questions is expressed prosodically, with yes/no-questions having a high-falling intonation on the question particle, and content questions having a high tone on the verb. If there is no verb, the high tone is realized on the predicate.

There are three main strategies for expressing possession; one for expressing familiar possession, one for expressing alienable possession, and one for expressing inalienable possession.

Familiar possession is expressed analytically by placing the possessor before the possessee, i.e. géga saxu ‘the man’s brother’. This strategy is being less and less used in the language, and is now confined to kinship terms and persons of important status, i.e. ‘my tribe’s leader’ or ‘my teacher’. Alienable possession is expressed using the comitative case. It is used for things that are in your possession but which are not a physical part of you, i.e. tools, clothes, and other objects. Inalienable possession is expressed with the locative case. It is used for things which are an intrinsic part of you, i.e. body part, thoughts, feelings, your children or very close friends.

Relative clauses are entire sentences that modify a noun. They precede the modified noun, and often look like adjectives from a European perspective. E.g. púka sámma would be translated as ‘the quiet bird’, but a more literal translation would be ‘the bird that is quiet’. You can even insert a pronoun before the verb, i.e. wo púka sámma ‘it is quiet, the bird’. An example of a transitive verb in a relative clause is ina woyi obwá sámma ‘the bird which I’ve seen’, or more literally ‘I have seen it, the bird’.

The most common way of expressing comparatives is by marking the thing being compared in the dative case, while using the adverb dzewu ‘above, exceeding’

(11) | initi | xugyítl | dzewu | áti |

1DU | 3COL-DAT | above | be.funny.NPFV.DIR | |

‘The two of us are funnier than all of them’ | ||||

Many verbs are semantically passive, and derive from the unproductive passive suffix -t. The productive construction is to put the auxiliary verb lá (from the verb xalá ‘to eat’, lwá in the perfective) after the verb in question, which is put in . It then takes all the verbal conjugation, while the other verb is then nominalized with the -k suffix. Its speech register prefixes are ku- for the domestic formal and xu- for the foreign formal. Other than that, it is regular.

Table: The passive auxiliary

DIR | INF | RPT | |

NPFV | lá | láné | lágu |

PFV | lwá | lwáné | lwágu |

INCH | láma | lámé | lámu |

PROS | lába | lábé | lámé |

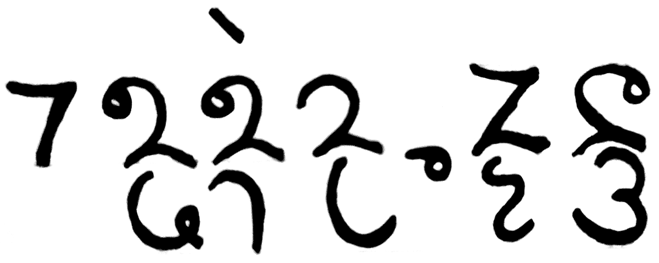

The Tsuma script is written from right to left. The script is syllabary-like, with onset consonants written below the following vowel. The system is at times ambiguous. For instance, the vowel <o> is treated as inherent, so a consonant without a vowel above is assumed to be followed by <o> or nothing. When a word begins in /o-/, a separate vowel letter is used. Clusters have to be written with silent vowels between the consonants The clusters Cw and Cy are written as <CuwX> and <CiyX>.

Syllables are structured into two row: the upper row and the bottom row. Unmarked consonant letters are assumed to be /Co/ or /C/ and are always placed on the upper row. However, when a consonant letter is followed by any other vowel, it is placed on the bottom row with a vowel letter on top. Consonant letters have “roofs”, which are horizontal strokes connected to the top of the letter. These are typically not written when the letter sits at the bottom row.

The script has various diacritics for marking certain phonemic qualities. Voicing may be optionally marked with a circle below the consonant sign. Vowel length is optionally shown with a dash above the upper row. Gemination is shown with a dash below the consonant letter. Pauses can be marked with a pause sign.

Table 14: Vowel markers of the Tsuma script mapped onto the vowel inventory.

Front | Back | |

High | ||

/i/ | /u/ | |

Mid | ||

/e/ | /o/ | |

Low | ||

/a/ | ||

Table 13: Consonant signs of the Tsuma script mapped onto the consonant inventory.

Labial | Coronal | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||

Plain | Lateral | |||||

Nasal | ||||||

/m/ | /n/ | |||||

Stop | ||||||

/p/, /b/ | /t/, /d/ | /kj/, /gj/ | /k/, /g/ | /ʔ/ | ||

Affricate | ||||||

/ts/, /dz/ | /tɬ/, /dɮ/ | |||||

Fricative | ||||||

/f/ | /s/, /z/ | /h/ | ||||

Sonorant | ||||||

/l/ | /j/ | /w/ | ||||

We can distinguish between symbols for consonants and vowels; the former are called consonant signs, while the latter are called vowel markers. This distinction between sign and marker is due to the status of the vowel symbols being somewhat weaker than that of the consonant; vowel markers usually have a consonant sign below, the exception being when words begin with vowels or when vowel hiatus occurs. Additionally, the vowel <o> is regarded as inherent (the ‘unmarked’ vowel) and is therefore never written, except in word-initial position and when it is long.

Table 15: Signs for stops and nasals and their original Ocogian signs

Stops | Nasals | ||||||

Tsuma | p | t | ky | k | x | m | n |

Ocogian | by [qʷʼ] | ti [t̺ʰ] | ki [cʰ] | gy [qʼ] | 'y [ʔ] | no [mɐ] | ny [n̺] |

Table 16: Signs for affricates, fricatives and sonorants and their original Ocogian signs.

Affricates | Fricatives | Sonorants | ||||||

Tsuma | ts | tl | f | s | h | w | l | j |

Ocogian | gjy [ʈ͡ʂʼ] | ty [t͡ɬʰ] | fi [ɸ] | zy [z] | hy [χ] | hu [χʷ] | ly [ɽ] | zi [ʑ] |

The Tsuma script is an adaptation of the Ocogian script, the language of the mountainous regions north of where Tsuma is spoken. Tsuma peoples probably first learned to write from Ocogian traders some 100 years ago, but it has been dramatically transformed in this period. The early system lacked uniformity and had not yet been standardized, but centuries of adaptations and modifications made by Tsuma writers has made it comparatively fit for transcribing the language. For the first decades only certain people learned how to write, and then usually only for very specific purposes like record keeping. These individuals had massive influence in shaping the script.

Table 17: Tsuma vowel markers and their original ocogian signs

Vowels | |||||

Tsuma | a | o | u | e | i |

Ocogian | a [ɐ] | o [ɔ] | u [ʊ] | e [ɛ] | i [ɪ] |

The version of the script used for writing Common Tsuma has now changed so much from the original Ocogian script that it is virtually unrecognisable for a speaker of Ocogian, though the general shapes of some signs still clearly show relatedness to their script.

The history of the Tsuma language can be divided into three linguistic periods. First is the period of Old Tsuma, which is the oldest traceable ancestor to the Tsuma language family. Of this period very little is known, other than that dialectal variation probably had not arisen yet. The second period is the period of Common Tsuma, which was the last stage at which all the dialects were still mutually intelligible. After this period, the dialects quickly diversified until mutual intelligibility was completely lost. This last period may be thought of as the period of diversification.

Table 18: Chronology of Tsuma

Year | Name of period | Significance |

200-400 | Old Tsuma | The language was unified and dialectal variations had not yet arisen. |

500-1000 | Common Tsuma | The last point in time at which the language was still unified. Dialects had begun to develop. |

1100-1600 | Language diversification | The dialects begin to develop into their own languages, and mutual intelligibility is lost. |

The phoneme inventory of Old Tsuma does not differ greatly to that of Common Tsuma. Old Tsuma had freer phonotactics, allowing for more consonant clusters. The consonant clusters later merged and assimilated into separate phonemes. The vowel inventory is also largely the same, with the exception of a vowel shift which merged merged old */e/ with */i/, and made */æ/ take the spot of older */e/. The consonant inventory of Old Tsuma is presented in Table 19, and the vowel inventory in table 20.

Table 19: The consonant inventory of Old Tsuma

Labial | Coronal | Dorsal | Glottal | |

Nasal | m | n | ŋ | |

Stop | p, b | t, d | k, g | ʔ |

Fricative | s, z | h | ||

Sonorant | w | l | j |

Table 20: The vowel inventory of Old Tsuma

Front | Back | |

High | i, iː | u, uː |

Mid | e, eː | o, oː |

Low | æ, æː | ɑ, ɑː |

Old Tsuma had a less restrictive syllable structure than what we see later. Though the general structure is still largely CV, meaning that word-final consonants were not possible, there were less restrictions on consonant clusters. The syllable template was (C(w/j)/P(s/z/l/j))V(ː). Geminates were permitted after vowels. Though vowel hiatus was not possible in Old Tsuma, it later came to enter the language through loan words. We can define three main types of syllables: CV(ː), P[s|z]V(ː) and PlV(ː)?

The origin of bare stems, o-stems and e-stems is quite simple; Old Tsuma */-o/ and */-e/ were lost when unstressed after most consonants. Yet, the vowel stayed before suffixes, such that the vowel seemingly reappears when the word is inflected. E.g. ‘stone’ is gán (Old Tsuma gáno) in the nominative, but gánoho in the locative. The other vowels were not lost word-finally, and these are referred to as bare stems. Some suffixes and clitics do not get /-o-/ or /-e-/ reinserted when they are attached to words, and instead get /-a-/. This is particularly the case for negational clitic =(a)du and the intensifier =(a)lu.

Prefixal metathesis

Old Tsuma did not permit most consonant clusters, and those that are permitted follow the sonority hierarchy. The first instance of metathesis happened to the pronouns *ina and *ite, which got prefixed and reduced to in- and it-. Whenever the word began with a consonant, they would get moved behind the initial consonant and inside the word stem itself. However, some of the possible clusters that would by the forms in- and it- were legal at that point, yet metathesis still persisted. This is likely due to analogy; a system where the prefixes would get metathesised was established, and all other forms were regularized to follow this system.

Table 21: Development of metathesised prefixes

Old Tsuma | Intermediary stage | Common Tsuma | Gloss |

*ina gáno | *in-gán | ginán | <1SG>rock |

*ite gáno | *it-gán | gitán | <3SG>rock |

*ina bliya | *in-liya | liniya | <1SG>animal |

*ite bliya | *it-liya | litiya | <3SG>animal |

Suffixal metathesis

Word-final coda consonants were never permitted in Old Tsuma, so when the accusative postposition i and the perfective marker u were reduced to clitics =i and =u (causing stress shift) and then being reduced to glides =y and =w, this was solved by shoving them inside the word-final syllable of the word stem; CVCVj, CVCVw > CVCjV, CVCwV. This, however, also messed with the stress system, as now you had short open syllables that were stressed word-finally (Tsuma, as discussed in section 2.3, has penultimate stress when there are no heavier syllables present). This was solved by lengthening the vowels of these syllables, which turns them into long syllables. These already naturally take stress in such positions according to the stress system.

Many old clusters had different reflexes in initial and medial position. When prefixes are added, the medial reflexes show up instead of the initial ones. From a synchronic perspective, this looks like a form of mutation whereby certain prefixes make certain consonants change.

Old Tsuma had no noun morphology, except for some derivational morphology. Case was instead expressed with postpositions, and plurality was optionally marked with the particle *ane.

The only verbal morphology that existed in Old Tsuma was the honorific prefixes. The perfective aspect was marked with the particle u.

Old Tsuma had a definite article *ke. It fell out of use quite early in history, but it is fossilized in the expanded demonstratives xwehuki and kwámoki. The latter is a newer analogical form created by analogy with xwehuki. Likewise, there is an analogical form kwámosa in analogy with xwehusa. The demonstrative kwám is relatively young, being created as a contraction of ku ám ‘this being’. An illustration of the development of these forms is shown in Table 22.

Table 22: The development of demonstratives, exemplified with the noun hima ‘fish’

Old Tsuma | Common Tsuma |

*hyima ‘a fish’ | ~> hima ‘a/the fish’ (definiteness distinction neutralized) |

*ke hyima ‘the fish’ | |

*wo ‘this’ | ~> wo ‘3SG’ |

*wo hyima ‘this fish’ | (superseded by ku hima ‘this/that fish’) |

*sa hyima ‘that fish’ | |

*xwæhu hyima ‘a fish which is present’ | ~> xwehu ‘this/that one’ (became independent in analogy with *wo) |

*xwæhu ke hyima ‘the fish which is present’ | ~> xwehuki hima ‘this fish’ |

*xwæhu sa hyima ‘that fish which is present’ | ~> xwehusa hima ‘that fish’ |

Ku is of uncertain origin, but it seems to be related to *ke. The form xwehu was originally a verb *xwæhu meaning ‘to be present’, often used in a relative clause before nouns. It was likely reanalyzed as a demonstrative in analogy with *wo ‘this’, which could occur both attributively and independently, hence why it occurs independently, unlike ku. xwehu is now counterintuitively never used attributively, possibly because this spot was eventually taken by ku and to fill the spot of *wo, which was generalized into the personal pronoun wo in Common Tsuma. This is now the regular 3-person pronoun in most dialects.

Monosyllabic verbs in Old Tsuma show remnants of a much older verbal paradigm where verbs exhibited subject-agreement. The most illustrative example is the verb *xu ‘to remember’:

SG | PL | |

1P | xuza | xuku |

2P | xuku | xuku |

3P | xusa | xuku |

This section discusses the daughter languages of Tsuma.

Káðoma is a descendant of eastern Tsuma dialects, as spoken in encampents around the mountain range north of the Liqak Empire. Like other daughter languages, the affricates have been lost, and in addition all the glottal sounds have been lost as well as the old vowel length.

A large-scale lenition changed the sound of the language drastically. The language gained new phonemes like /ʃ, ʒ, f, ʋ, ð, x, ɣ/ and phonemic vowel length from contraction of sequential vowels. A change that made Káðoma stand out was the waves of syncope that deleted many vowels, giving syllable shapes that previously were not possible earlier in the history of Tsuma.

Grammatically, Káðoma is relatively archaic, keeping most of the cases and even gaining a new "comparative" case, whilst verbs have gained personal conjugations from affixed pronouns. These affixed forms settled before the old pronouns shifted around making them differ significantly from the old language. In addition, the old evidentiality system has been replaced by a new mood system. New tenses for the future and various past tenses have also developed.

Napanü developed from a mixed dialect, though there is a lot of uncertainty. The language lost many phonemes originally found in Common Tsuma, like all the affricates, the lateral affricates, the glottal stop and the voiced stops. In turn, it has gained a great deal of new distinctions, like post-alveolar fricatives /ʃ, ʒ/, a trill /r/, the voiced fricative /v/ and uvular consonants /q, χ/. The length distinction in vowels was lost, but in turn, three new central vowels /ɨ, ʉ, ə/ were innovated.

Grammar-wise, Napanü has changed a lot from its Tsuma roots. The old aspectual and evidential distinctions have been transformed into a tense-mood system, where the old reported and inferred evidential categories became a new subjunctive mood, and the imperfective, perfective and inchoative turned into new present, past and future tenses respectively. Napanü also innovated a large number of person prefixes for verbs, which mark both the subject and the object. Many of these innovations are shared with Káðoma, but overall, Napanü is not nearly conservative.

This is a list of all changes, both grammatical and phonological, from Old Tsuma to Common Tsuma.

t, d > [͡ts, d͡z] / _i

k, g, kj, gj, ks, gz > [c͡ɕ ɟ͡ʑ]

k, g > [c͡ɕ ɟ͡ʑ] / _i

ŋ > [g] / V_V

tw, dw > [p, b] / V_V [+rounded]

hw > [w] (elsewhere)

[c͡ɕ, ɟ͡ʑ] > [c, ɟ] (in central dialects)

[c͡ɕ, ɟ͡ʑ] > [͡tʃ, d͡ʒ] (in western dialects)

hj > kj / #_

hj > [j] / V_V

Taken from David J. Peterson’s The Art of Language Invention. Shorter, more everyday equivalents are given in parentheses.

Hayi obá! (Obá!) | 2SG<ACC> see | Hello! (lit. I see you!) |

Xinéku anihabayune ogyi (Ogyi) | <1SG>wish PL-2SG-dream long.IMP.DIR | Goodbye (lit. I wish you long dreams) |

PL-2SG-dream long.IMP.DIR INT | How are you? (lit. Have your dreams been long) | |

Yánat (Nat) | be.true.IMP.DIR | Yes (lit. It is true) |

Yánat oz (Toz) | be.true.IMP.DIR NEG | No (lit. It is not true) |

Xwehu dligyálu! | this be.good.IMP.DIR=INTS | Excellent! (lit. This is great!) |

Woyi enwa. | 3SG<ACC> know | It is known. |

Tsigéga ogu. | COL-male die.IMP.DIR | All men must die |

Kinád anixiniddzibye. | <1SG>sun PL-<1SG>star-COM | My sun and stars. |

Dagyal inatl. | moon 1SG-DAT | Moon of my life. |

Hayána uma o? | 2SG-ability speak.IMP.DIR INT | Do you speak Tsuma? (lit. Do you speak?) |

Ina tílegy (tílegy) | 1SG hungry.IMP.DIR | I’m hungry |

Xinaswa hatl gunu | <1SG> heart 2SG-DAT beat.IMP.DIR | I love you (lit. My heart beats for you) |

Haxéku inabye bagúyu o? | 2SG-wish 1SG-COM REFL-bind INT | Will you marry me? (lit. do you want us to bind ourselves) |

Pówu ánapyú/ánapúgy ígaleko, okyíli ánapú okkuho mádzat. Dádákoho okyíliho kolok, ga okkuho wo ogyi máz. Nabígáxayi o?

pówu ánap<y>ú/ánapú-gy ígal-eko, okyíli ánapú okku-ho mádzat. dá~dák-oho okyíli-ho kolok, ga okku-ho wo ogyi máz. na-bígaxayi o

Water hill/hill-ACC leave-IC, man hill head-LOC sit.IMPF.DIR. DU~hand-LOC man-LOC stick, and head-LOC 3SG be.long feather. 1PL-chieftain INT?

“A man sits on a hill as water runs from it. He has a stick in his hands, and he has a large feather on his head. Is he our chieftain?”

Central pronunciation

[ˈpoːβʊ ˈaːnapjuː ˈiːgaləkɔ, ɔˈciːlɪ ˈaːnapuː ˈokːʊχɔ ˈmaːd͡zat. ˈdaːdaːkɔχɔ ɔˈciːlɪχɔ kɔˈlok, ga ˈokːʊχɔ wo ˈoɟɪ maːz. naˈbiːgaːʔaʝɪ o]

Western pronunciation

[ˈpoːbʊ ˈaːnapuːd͡ʒ ˈiːgaləkɔ, ɔˈ͡tʃiːlɪ ˈaːnapuː ˈokːʊχɔ ˈmaːd͡zat. ˈdaːdaːkɔχɔ ɔˈ͡tʃiːlɪχɔ kɔˈlok, ga ˈokːʊχɔ wo ˈod͡ʒɪ maːz. naˈbiːgaːʔaʒɪ o]

Eastern pronunciation

[ˈpoːβʊ ˈaːnapjuː ˈiːgaləkɔ, ɔˈc͡ɕiːlɪ ˈaːnapuː ˈokːʊχɔ ˈmaːd͡zat. ˈdaːdaːkɔχɔ ɔˈc͡ɕiːlɪχɔ kɔˈlok, ga ˈokːʊχɔ wo ˈoɟ͡ʑɪ maːz. naˈbiːgaːʔaʑɪ o]

This is a translation of the text in Image 1.

Anópi | tságyelu | xwehiyú, | enwa | o? |

an-ópi | tságye=lu | xweh<y>u | enwa | o |

PL-fly | taste.well=INTS | this<ACC> | know | INT |

“Flies taste great, did you know?” | ||||

Nyéwe | xwehiyú | enwadu | woka | tsinyéwe |

nyéwe | xweh<y>u | enwa=du | woka | tsi-nyéwe |

people | this<ACC> | know=NEG | therefore | COL-people |

“People do not know this, and that is why they are all-” | ||||

bíxo | pikyinélu. | Ina | anópyi | xalátl, |

bíxo | pikyi-né=lu | ina | an-óp<y>i | |

often | be.sad-IMP.INF=INTS | 1SG | PL-fly<ACC> | eat-PRP |

“so very sad. This is the reason why I eat flies,” | ||||

tsixodu | pikyuwí. | Inatl | tólibwo! | |

tsixo=du | piky<w>i | ina-tl | tólib<w>o | |

always=NEG | be.sad<PRF.DIR> | 1SG-DAT | imitate<PRF.DIR> | |

“so that I shall never have to feel sadness.” | ||||

xógoleho nyéwe eokyú bálwagu ga bísyégiyu kyótigu.

[ˈʔoːgɔləχɔ ɲeːwə əɔc͡ɕˈuː ˈbaːlwagʊ ga ˈbiːsjeːgɪʝʊ ˈc͡ɕoːtɪgʊ]

north-LOC people cheese<ACC> trade-NPV.RPT and world-ACC contemplate-NPV.RPT

“It is said that the people of the North trade cheese and ponder the world.”

and east-LOC people-COL AUG-murder-NPV.RPT and be.hard-NPV.RPT. 1PL-people-ABL 3PL-land<ACC> travel.to-NPV.RPT. people=NEG return.

“The Eastern peoples however, are said to be warrish and brutal. Many amongst ourselves have wandered into their lands and never returned.”

If you do the effort of transcribing and attempting to translate the texts shown in these images, you might find that some of them are outdated. Especially Image 5 is probably very out of date. The writing system has not changed however, so they still serve as illustrations of the script in use.

Image 3: Frog

Image 4: Mountain

Image 5: Dead tree

Abbreviations | |

n. | Bare stem noun |

n.o. | O-stem noun |

n.e. | E-stem noun |

vi. | Bare stem intransitive verb |

vt. | Bare stem intransitive verb |

vi.o. | O-stem intransitive verb |

vi.e. | E-stem intransitive verb |

vt.o. | O-stem transitive verb |

vt.e. | E-stem intransitive verb |

adv. | Adverb |

ptc. | Particle |

pp | Postposition |

pf. | Prefix |

pron. | Pronoun |

conj. | Conjunction |

int. | Interjection |

OT | Old Tsuma |

CD | Common Doan |

CP | Classical Pakesia |

Page of

[1] The rules of suffixal metathesis sometimes create illegal clusters, which are solved by inserting an epenthetic vowel. This is why there is an /i/ in tuwiyá. See section 2.3.

[2] The following vowel is /u/ for /w/ and /i/ for /j/.

[3] Only when the mutated form is /j/

[a]example pls

[b]only /h/ > /j/? what about /h/ > /w/ and /kj/ > /j/?

[c]this has a historic reasoning behind it, which if I remember correctly is that the dual arose before VhjV >VjV took place but still after VhwV > VwV.

In retrospect I think that might be a bit strange, you'd expect those changes to occur at the same time since they're the same type of sound change, but I think it can be justified by the allophones of /h/, i.e. /hw/ [χw] is possibly easier to lose first and then /hj/ [çj] is lost later, but idk if that makes sense

(I should probably make note of this in the doc)

[d]Checked the list of changes and yes this is why

also yes it should apply to /kj/

[e]this word sounds ridiculous

[f]neidå